Ashdod, Israel – With the dawn of the cell-cultured seafood making waves, a new player has landed. FoodTech start-up Forsea Foods, Ltd. announces it has brought this novel concept closer to natural perfection through its patented organoid technology.

Previously used in developmental biology, medicine and research, organoids are stem cell-derived, three-dimensional tissue structures that when used in cell-cultured seafood products requires only a minimal amount of growth factors. The start-up announces it is kicking off its activities by targeting the supply gaps in the eel meat market

Developed by Iftach Nachman, PhD, co-founder of Forsea, the organoid approach to forming fish tissue involves creating an ideal environment for fish cells to spontaneously form their natural composition of native fat and muscle. They grow as a three-dimensional tissue structure in the same manner they would grow in a living fish

Cell-culturing fish the organoid way

Cell-culturing fish the organoid way

“While cell cultivation largely focuses on a system of directed differentiation, where cells are signaled to differentiate into a specific cell type and are then combined on a scaffold, our system grows the aggregate of the various cells already at the initial stage of the process. The cells organize themselves autonomously into their innate, purposed structure, just as in nature,” explains Nachman, a principal investigator at Tel Aviv University.

The result is sustainably produced, succulent filets of cultured seafood that embody the same taste and textural traits as their ocean-caught counterparts. Unlike those counterparts, however, the resulting product is free from pollutants such as mercury, industrial chemicals, and microplastics. Forsea claims that they will also yield the same nutritional profile as traditionally raised seafood. “This is a function of how you nourish the cells,” asserts Roee Nir, a biotechnologist and CEO and co-founder of Forsea.

“There are multiple benefits to the organoid method of cell cultivating fish,” Nir adds. “First, it is a highly scalable platform that bypasses the scaffolding stage and requires fewer bioreactors. This makes the process much simpler and more cost-effective. Additionally, it dramatically reduces the amount of costly growth factors needed.”

Nurtured by the The Kitchen FoodTech Hub, the start-up was formed last October, with an initial injection of capital support from the Israeli Innovation Authority (IIA) and the Strauss-Group. The new venture brought together Nir, Nachman, and Yaniv Elkouby, PhD, a senior researcher at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and expert in cell developmental biology who dedicated numerous years studying piscine biology.

Not so plenty of fish in the sea

Not so plenty of fish in the sea

“The demand for seafood is showing no signs of slowing down,” asserts Amir Zaidman, VP Business Development of The Kitchen Hub. “In fact, global demand is projected to almost double by 2050. But we are rapidly approaching the point where there will simply not be enough fish in the sea to sustain the global community. Forsea’s innovative new cultivation platform has the potential to bring positive disruption to this paradigm by providing a clean, nutritious, delicious, and commercially viable alternative to wild-caught seafood while leaving the delicate ocean ecosystem completely untouched.”

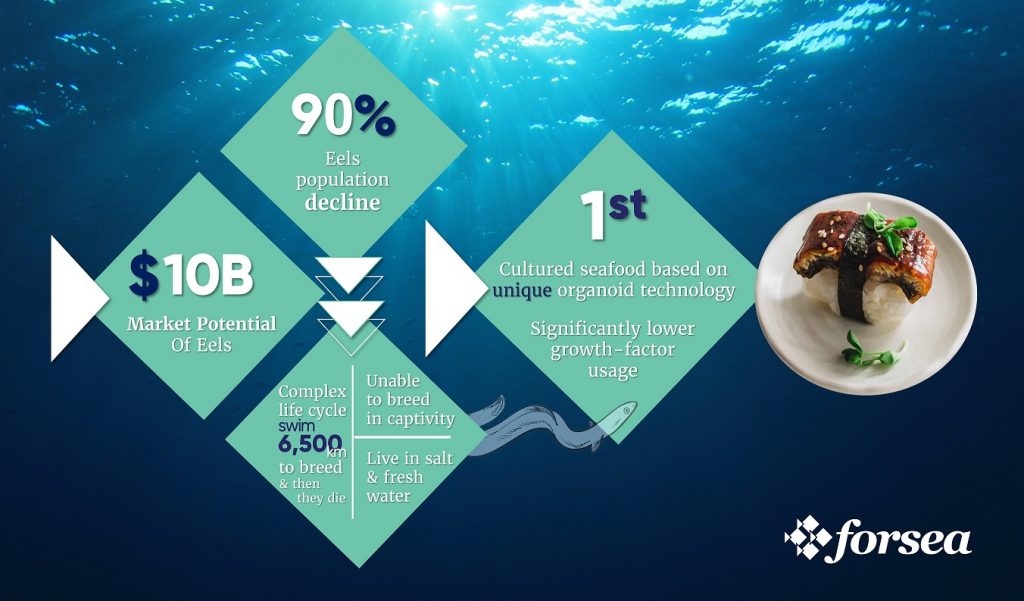

While Forsea can cultivate practically any type of seafood, the company says it is currently focusing its efforts on cultivating the meat of freshwater eels. “Eels are a much sought-after delicacy, especially in East Asia. Yet overfishing in the past decades has rendered them an endangered species. The Japanese eel population alone has declined by 90 to 95 percent, which has driven prices to astronomical levels. Eel meat sells in Japan for up to US$70 per kilogram. They are also considered to be the ocean’s most mysterious creatures, undergoing an unusual metamorphosis,” reveals Nir.

The Mysterious Life of Eels

A most striking feature of eels is that they cannot breed in captivity, making it all the more complex to raise them for food. Eels live most of their lives in sweet water and, when ready to procreate, will swim 6,500 km into the deep ocean to either of two very specific meeting points: the Sargasso Sea, near the Bermuda Triangle, or off Guam. And once they breed, they die. What returns with the help of the ocean’s currents are two-gram sized baby eels. These can be fished and raised in controlled pools where, over the course of a year and a half, they turn into 250g adults.

“The market demand for eels is enormous,” adds Nir “In 2000, the Japanese consumed 160,000 metric tons. But due to overfishing and rising prices, consumption has dwindled to just 30,000 metric tons. There is a huge gap between the supply and the demand for eels which traditional aquafarming cannot accommodate. Compounding this problem, Europe has barred the export of any type of eel product. “The market opportunity for cell-cultured eels is tremendous,” concludes Nir.